Even if you’re not a sports fan, chances are you’ve seen basketball coaches call a time out and draw up plays as they strategize to beat their opponents. Hollywood movies have taken us inside a football locker room where coaches have drawn up game-winning plans. Likewise, farmers develop a playbook for each season.

Even if you’re not a sports fan, chances are you’ve seen basketball coaches call a time out and draw up plays as they strategize to beat their opponents. Hollywood movies have taken us inside a football locker room where coaches have drawn up game-winning plans. Likewise, farmers develop a playbook for each season.

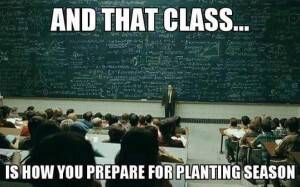

This past week Mohn Family Farms shared a photo of a huge chalkboard filled with facts and figures, implying that farmers must take a lot of information into consideration when preparing for the planting season. Also this week on Rural Route Radio, broadcaster Trent Loos asked why farmers don’t raise something else if they’re certain to lose money on a crop before it even goes in the ground.

I’ll begin by trying to answer Trent’s question first… “Switching gears” by planting another crop or raising another type of livestock may seem like a logical choice until a person takes a closer look at what that would actually entail. Different types of crops and different species of animals require different types of equipment.

Until the 1950s and 60s, most farms were quite diversified. It was common for a single farm to raise chickens for meat and eggs, dairy cows for milk, beef cows, hogs and crops including corn and alfalfa for hay. Keep in mind that families also were larger, so available manual labor meant farmers didn’t have to make very big investments in equipment.

Farming practices and family dynamics changed over time. Equipment replaced farmhands. To become more efficient and to prevent money from being tied up in underused assets, many farmers like me became more specialized. I’m now set up with equipment to raise corn and soybeans. If I were to change to another crop, like alfalfa, I’d need additional equipment to harvest and bale hay. I’d also need a different building for storage since bales won’t fit into my grain bins.

Deciding to raise livestock can’t be a spur-of the-moment decision as it requires certain facilities and possible pasture ground. I’ve given some thought to raising beef cattle, sheep and turkeys. All of these would require a sizable capital investment as I don’t have the facilities needed to house these types of animals. Even though sale prices are strong now for many of these animals, keep in mind that markets are cyclical. I’m looking for opportunity, but I have to be realistic.

If I’m being realistic, why would I plant a crop if I’m expecting to lose money on it? I was asked that great question last fall when I was speaking to a class of sixth graders without farm experience. Here’s my answer, “Farmers are by nature optimists with much faith.”

I have faith that when I plant a seed, a plant will grow. When you do the math, you’ll see that I would lose more money by not planting anything at all. Here are example costs on a per acre basis:

| Rent | $250 |

| Fertilizer | $200 |

| Seed | $120 |

| Crop Protection | $35 |

| Total | $605 |

An average corn yield is 175 bushels per acre (bu/A). If we take that yield times the commodity price of $3.50 per bushel, I would pretty much break even given that I already have the machinery and equipment needed. Now if I don’t plant any corn, I still owe rent and am out $250 per acre.

Please note this is really simplified version of input costs, and all farmers face different situations. Some farmers own their equipment while others have equipment leases; some farmers rent some ground while others own all of their ground. The point of this exercise is to show that farmers take the risk of planting a crop based on the hope of a much better outcome.

Now let’s talk about that chalkboard…

I start thinking about planting my next crop before the current crop is even harvested. I consider how what I did for the current crop is working: How are my seed varieties performing? Did I place them correctly? There are hundreds of seed choices suitable for different situations. Considering seed options could fill one chalkboard!

Different soybean varieties and corn hybrids have different levels of resistance to types of insects and disease, which makes them more “defensive” in nature. Defensive genetics can handle stress like plant disease better and tend to be consistent performers year after year, but you’re giving up the potential for top-end yield when you plant them. Other racehorse varieties will give you fantastic yields when growing conditions are ideal for that variety, but yields will be less than desirable in challenging growing conditions. That’s why it’s important to consider the options when selecting seed and manage risk with a crop plan.

Some types of soybean varieties and corn hybrids perform better on different types of ground. There are hundreds of soil types in Iowa, and my farm has many different soil types in the same field! How do you pick a variety that will give you the maximum yield across that whole field? Another chalkboard filled.

New technology has produced a planter that will plant different varieties as a farmer goes across his field, but that technology costs. We could fill another chalkboard by doing the math!

Fertilizing fields and treating for pests brings government regulation into play. All pesticides must meet certain requirements for safety. If you use “natural” fertilizer from your livestock, plan on another chalkboard to meet those regulations! Farmers must take soil and manure sample tests. Then those test results must be matched with the soil types.

Then there is the decision of tillage: no tillage, minimum tillage or vertical tillage. Should you plant cover crops?

All of these factors must be considered before farmers plant the next crop, so… one chalkboard isn’t big enough!